On the Mountain Lion in Griffith Park

Adjusting to a Lion in Their Midst: After the city posts signs warning of recent sightings, some hikers in Griffith Park take steps to alter their routines.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2004.

As dawn broke over Griffith Park on Saturday, hikers and cyclists faced a new reality: A mountain lion had returned to an area where such beasts were presumed vanquished years ago.

And some people came ready to rumble.

Wielding her handsomely carved walking stick, Ann Howard, 63, said she was ready to thump a lion, should it pounce.

“I don’t really expect it to do any good, but it gives me a sense of security,” said Howard, who was walking alone on the Mt. Hollywood trail.

“I don’t really expect it to do any good, but it gives me a sense of security,” said Howard, who was walking alone on the Mt. Hollywood trail.

Los Angeles long ago earned a reputation as a paved-over paradise, and some wildlife experts expressed surprise that a lion, also known as a cougar or puma, could find its way into a park completely surrounded by freeway and city.

Visitors, too, seemed impressed and in some cases both happy and a little fearful about the discovery.

A frequent visitor to the park, Howard said that on Saturday she saw about 10 other women carrying hiking sticks — something she didn’t see two weeks ago.

“It’s a fabulous park; we’re lucky to have it here in the city,” she said. “If the lion came here to live, that’s fine with me.”

That was not a sentiment shared by others.

“We’re not discriminating against lions — we don’t want bears here either,” said Mike Johnson, 62, a teacher from Long Beach who was hiking to get in shape for an upcoming trip to the Rocky Mountains.

“They do have a place in nature, and I don’t want to see them go extinct here — they’re beautiful creatures,” he added. “Any place that is wilderness you want to be as natural as possible, but heavens no — this is not wilderness.”

Johnson thought that, if possible, the lion should be captured and relocated. His fear is that Griffith Park draws an urban crowd unused to hiking in lion country.

Jane Kolb, a spokeswoman for the city parks department, said rangers would continue to take a wait-and-see approach with the lion. She said she was in the park Thursday night and spoke to many hikers, most of whom were intrigued by the news of the cougar and wanted to see it.

She said other wildlife agencies agreed “that this lion isn’t bothering anybody, and we don’t need to bother it.”

Kolb said that should the lion exhibit dangerous behavior, the parks department would notify the state Department of Fish and Game, which could kill the cougar on the basis that it was a threat to public safety.

Fish and Game officials said the agency did not relocate adult lions because they were often killed by other lions already established in the area of release.

“I am personally concerned that such a strong animal found its way to the park,” said Tom LaBonge, the Los Angeles councilman whose district includes Griffith Park. “This isn’t Yosemite … but would it be right to go out and hunt the lion at this point? No. The right thing for us is to go make the public aware of it.”

Toward that end, the city erected signs last week at many trailheads warning visitors that mountain lions lived in the area.

But not everyone saw the signs.

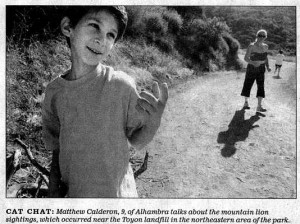

Tiaran Gorgorian, 54, of Glendale was riding his bike next to the old landfill when he was informed by a reporter that a mountain lion had been on the prowl in that part of the park — and, in fact, there were tracks nearby possibly belonging to a cougar.

After digesting the news for a moment, Gorgorian cheerfully shrugged and said, “I don’t want to be meat,” before pedaling off — perhaps a little quicker than before.

A question that remains is where the lion came from. There are two possibilities: the Santa Monica or Verdugo mountains.

The National Park Service has captured two lions in the Santa Monicas and outfitted them with radio collars so the agency can track them, according to Ray Sauvajot, the chief of planning, science and research management for the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

But neither cat has gone east of the 405 Freeway, Sauvajot said. Two other lions with collars are living in the Simi Hills and the Santa Susana Mountains, respectively.

Lt. Martin Wall, a state Fish and Game warden, said that in recent years he had seen plenty of lion tracks in both the San Gabriel Mountains and the Verdugos, and that the lion could have crossed from the Verdugos into Griffith Park via concrete drainage channels.

Paul Beier, a Northern Arizona University professor of wildlife ecology, did some of the pioneering work on cougars in the Santa Ana Mountains in the 1990s. He was almost at a loss for words when informed about the lion in Griffith Park.

“That’s an awfully small area for a mountain lion to spend time in,” he said. “He can’t get out except the way he came in. Let’s hope it finds its own way back.”

Beier guessed that the animal was a young male that had been squeezed out of its range by adults, or that it had landed in the park after an exploration gone awry.

Hector Vera, 44, wasn’t interested in scientific ponderings about the lion.

“This is their home here. We invaded this place,” said Vera, of Loz Feliz, while hiking Saturday. “I don’t think they’re a dangerous animal if they’re left alone.”

His partner, Felipe Venegas, 34, disagreed. Venegas recalled how their housecat Juanita had scratched a pair of expensive stereo speakers and sometimes acted a tad too aggressive.

If a little cat couldn’t always be trusted, Venegas said, then what about a big wild one?